MOVING, THROUGH TIME

Today, standing on any pedestrian bridge crossing San Jose Ave, you’ll see multiple lanes of traffic, transit rails, and bike lanes before you…

Imagine that in 1776 a Spanish Expedition named thatthis route El Camino Real to mark a contiguous path stretching from Mexico to the tip of the peninsula. On their way to establish the Presidio, the Franciscan fathers had only stumbled upon a well-used walking path through a natural dip, or saddle, trod for thousands of years by the Ramaytush Ohlone and other visiting indigenous communities, the lowest point in the landscape between two rising hills.

Imagine that from 1862 until 1922, you could reach out and almost touch the crumbling cliffs on either side of the 25 foot wide path, but you might have to jump out of the way of a black-smoke belching railroad train, using rails that took the Southern Pacific RR on its only overland route to San Jose. If you listened hard enough in the space between trains, you might be able to hear Serpentine/Precita Creek to your north, Islais Creek to the south, and the gush of water through Spring Valley Water Company’s flumes, taking potable water up to the reservoir near Holly Park.

Imagine that in the 1870s you had just come out of the 4 Mile House at today’s Randall Street to travel the parallel Old San Jose Road south in search of a lot to buy in the newly established Fairmount Heights, but not before you picked up some fresh milk or butter at Mitchell Dairy at 29th and Noe Streets. Imagine you could step onto streetcars from your front steps.

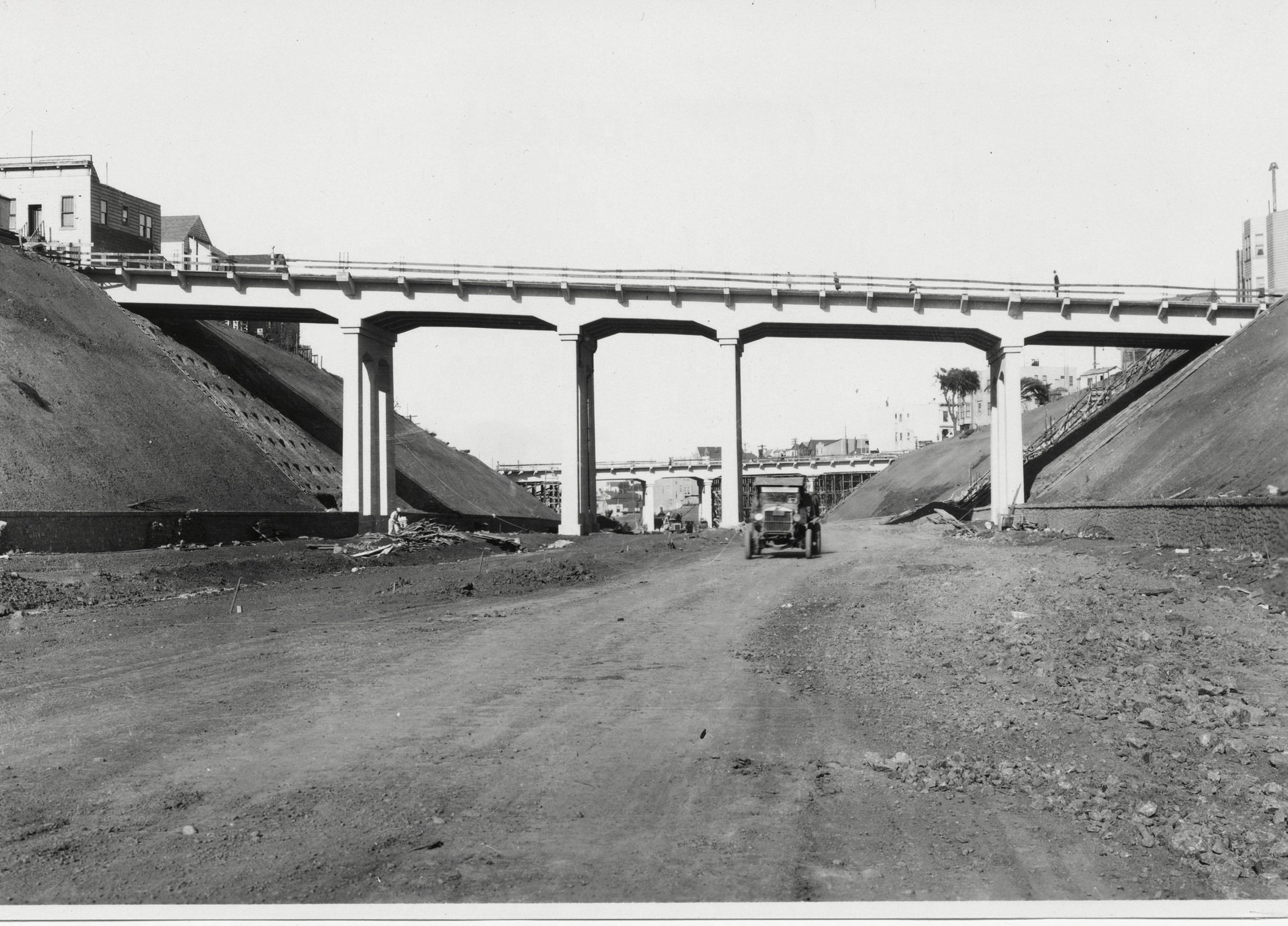

Imagine you were City Mayor Rolph needing to respond to something called the automobile taking the country by storm, and you had grand plans of annexing towns on the peninsula to the south, so you oversaw 256,276 cubic yards of earth taken out and hills scraped and houses moved (or destroyed) to result in a roadway totalling 117 1/2 feet in width accommodating a double track steam railway and a double track street line, thereby “providing additional means of vehicular traffic to the peninsula towns.”

Imagine that the population of this urban center grew and grew and saw the 280 freeway added in 1964. And since the movement of people in this urban center was predetermined to require more than car routes, in the 1990s the J-Church line echoed the sounds of streetcars that ran along here almost a century prior, and in the 21st century a separated bicycle lane became a reality, where cyclists could safely head south and west and enjoy the stewarded pathways on either side of the Cut, greenery replacing what once was a disturbed landscape.

Next time you cross San Jose Ave, imagine that all of this happened, right here where you stand.